Newspapers in North America are in a state of flux and the entire industry is a cacophony of mergers, acquisitions or bankrupt companies. Ailing advertising revenue is prompting many local, regional and major papers to adopt the New York Times Paywall strategy, to varying amounts of success. The Washington Post was sold to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and general upheaval has forced The Rocky Mountain News into the abyss, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, reduced to a bare-bones internet operation.

What makes Japan so different from their counterparts in the USA and Canada? You rarely hear about mergers and acquisitions or longtime papers forced into bankruptcy.

Professor Hayashi Kaori of the University of Tokyo said that “Newspaper circulation figures remain remarkably high in Japan. Among the major national papers, the Yomiuri Shimbun — Japan’s largest — puts its circulation at slightly less than 10 million. The number two, Asahi Shimbun, has an official circulation just shy of 8 million. Japan’s regional newspapers typically reach 50 percent of households in their market, and a fair number boast a penetration rate of 60 percent or higher. Moreover, Japanese regional papers are almost all independently operated — unlike their US counterparts, which are mostly owned by nationwide newspaper chains like McClatchy.”

Newspapers in North America have seen dramatic declines in both circulation rates and advertising revenue. Nearly two-thirds of the 25 largest papers in the U.S. posted circulation declines of 10% or more in 2011 alone. Japan has only seen a 20% decrease in the last 15 years.

How does Japan remain so stable? Hayashi Kaori explains, “The chief reason is that for most Japanese adults over a certain age, newspapers not are merely an information medium but an integral part of their lifestyle. If you are an adult in Japan, chances are that one of the first things you do after getting up in the morning is to go to your mailbox and collect your morning paper. Later, when the evening newspaper arrives, you scan the headlines to catch up on the day’s events. Japanese readers remain loyal to one newspaper or another simply because their family has always subscribed to that newspaper, or because they happen to know the neighborhood distributor.”

The Youth are moving towards Digital

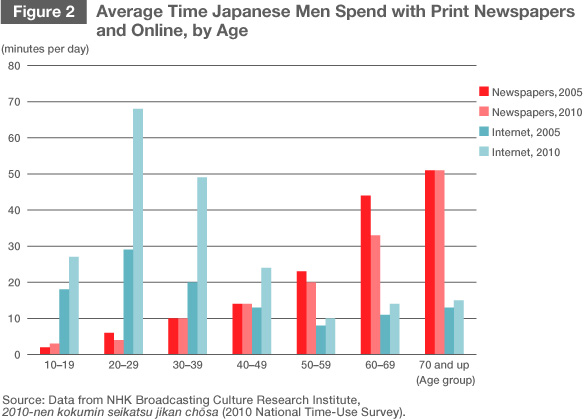

We live in a world where most of the breaking news occurs on Twitter, Facebook and Reditt. No matter what subject interests you, there are dedicated websites, blogs or forum communities devoted to it. The Figure above is data from a survey conducted in 2005 and 2010 by the NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute. In 2010, men in their twenties reported spending four minutes per day with a print newspaper on average, as compared with 68 minutes online. Most often, if youth are getting their news from a digital source, they are very unlikely to embrace print as they grow older. This creates a problem where subscription circulation remains steady, but there is a severe lack of new signups.

Many of the leading Japanese newspapers have not embraced a digital format yet, chiefly because of their extensive distributor base and people reliant on them for an income. If the newspapers start to move into a digital direction there would be a backlash from the traditional subscription base and everyone involved in the manufacturing and distribution pipeline. Some newspapers are starting to move into digital, slowly, but have not yet embraced it.

Yomiuri, Japan’s largest daily newspaper, makes its paid digital edition, Yomiuri Premium, available only to print subscribers. Similarly, the Asahi Shimbun and the Nihon Keizai Shimbun hype their print-plus-digital packages, but discourage digital-only subscriptions by pricing them almost as high as print subscriptions. Most regional newspapers, meanwhile, have balked at publishing a digital edition. Their websites carry only free content in the form of “article teasers” designed to spark interest in the print edition.

The newspaper industry in Japan is stable and has been somewhat immune to most of the trends plaguing the North American market. They have an aging, but loyal core-base of readers, where cultural values sustain the industry at large. The entire industry has nothing to worry about in the immediate future, but a problem may arise in 10 years from now, when the youth of today are the adults of tomorrow and have children. If the trend continues of reading more digitally and only spending a few minutes a day with a physical paper continues, Japan may be in big trouble.

Michael Kozlowski is the editor-in-chief at Good e-Reader and has written about audiobooks and e-readers for the past fifteen years. Newspapers and websites such as the CBC, CNET, Engadget, Huffington Post and the New York Times have picked up his articles. He Lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.