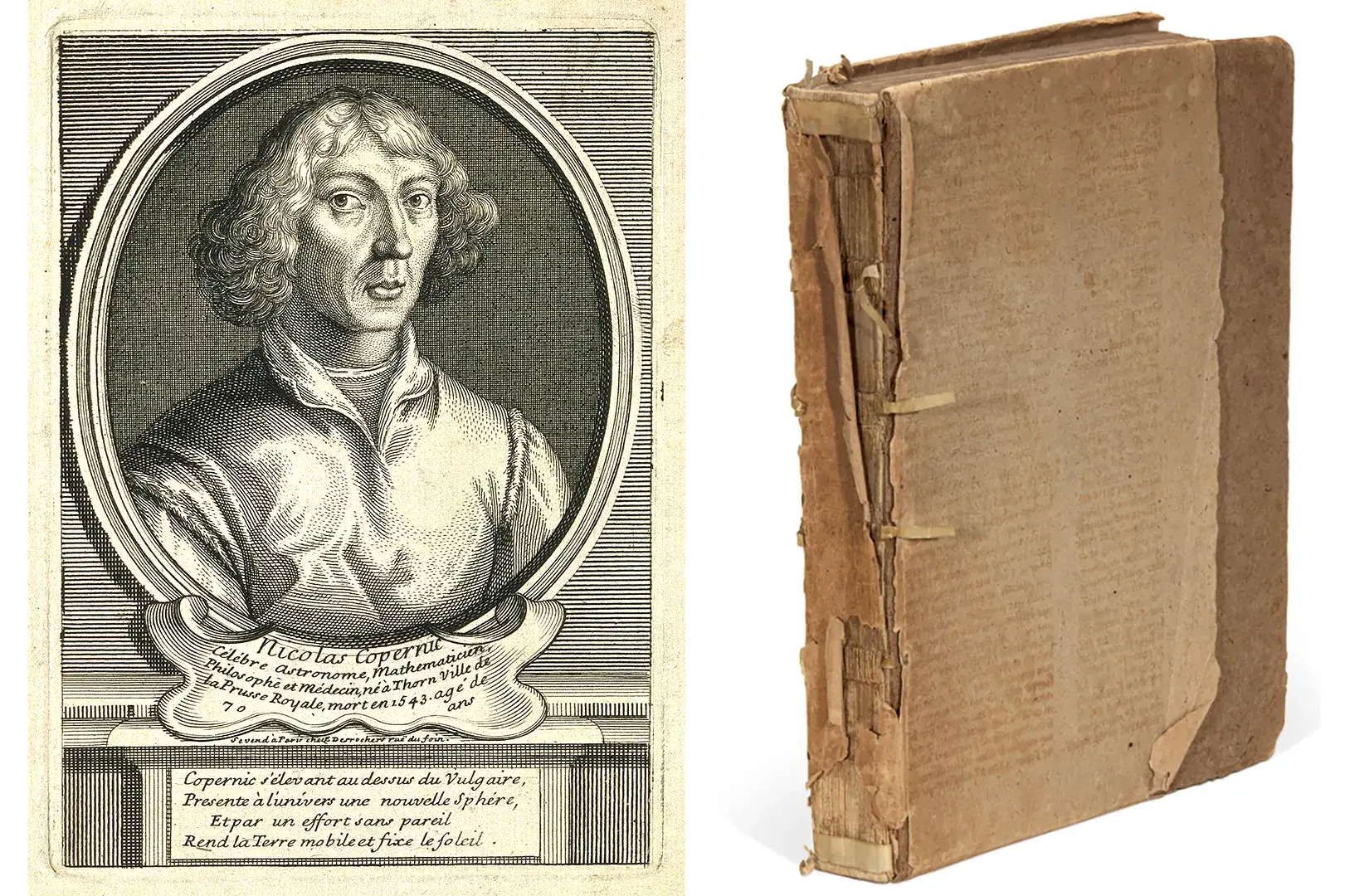

It was in 1543 that Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus challenged the 1,400 year dominance of Ptolemaic cosmology when he published De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres). A rare, pristine first edition of his manuscript is now for sale for $2.5 million, suggesting that the Sun is at the center of the Solar System and not the Earth. As a consequence of his manuscript, our entire view of the Universe and our place within it has been altered.

It was in 1543 that Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus challenged the 1,400 year dominance of Ptolemaic cosmology when he published De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres). A rare, pristine first edition of his manuscript is now for sale for $2.5 million, suggesting that the Sun is at the center of the Solar System and not the Earth. As a consequence of his manuscript, our entire view of the Universe and our place within it has been altered.

Christian Westergaard, who is handling the sale for Sophia Rare Books, maintains that the high price tag reflects not only the importance of this work from a historical perspective but also the fact that this particular edition possesses an excellent provenance. The edition will be displayed at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair next month. An identical copy with a few repairs and a contemporary binding sold in 2008 for $2.2 million. However, the majority of first editions of De Revolutionibus that are on the market are illusory, have fake bindings, facsimile pages, or have been altered in such a way that the value is diminished.

According to Owen Gingerich, a leading Copernican scholar who investigated and found 276 copies of De Revolutionibus (of approximately 500 originally printed) around the world over the course of 35 years. Among the 276 copies he found, most of them belong to educational institutions. In 1496, Nicolas Copernicus visited Italy to study canon law and medicine, but in March 1497 he witnessed his first lunar eclipse, which convinced him that astronomy was the future of his life. Copernicus was raised by his uncle, a canon at Frauenburg Cathedral. In the turret of the town’s walled fortification, Copernicus built an observatory for him, where he diligently studied the heavens each evening. He eventually became a canon.

Several astronomers, including Copernicus’ personal friends, circulated one anonymous booklet in 1514. It is well known that his new model of the universe revolves around the Sun, with the Earth and other planets orbiting around it, as described in his Little Commentary. He correctly located Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter, and determined that their positions were influenced by the rotation of the Earth.

In these proverbs, he composed De Revolutionibus, which was not published until the very end of his life. Following a visit by a young professor of mathematics and astronomy named Georg Joachim Rheticus at Frauenburg in May 1539, Copernicus completed the manuscript at his suggestion. A Lutheran theologian based in Nurnberg, Andreas Osiander, was assigned supervision of Rheticus’ book in 1542 after it was delivered to a printer in Nurnberg.

Osiander was alarmed by Copernicus’ potentially unorthodox content, and therefore substituted his own unsigned preface. According to him, the book’s conclusions are not the “truth,” but rather a new model for calculating the positions of heavenly bodies using a simpler method. Rheticus never forgave Osiander for what he perceived as a betrayal, even marking several copies with a red crayon to indicate that the replacement preface was not to be trusted. Osiander and others found the heliocentric universe to be unorthodox. In implying that the Earth was stationary, the Ptolemaic worldview was seamlessly woven with traditional interpretations of certain passages in the Bible, which the Church had declared as unerring.

The manuscript of De Revolutionibus arrived to Copernicus in May 1543 at the end of a stroke, which left him partially paralyzed. The legend is that he woke up from a coma, looked at his book, and died peacefully of a cerebral hemorrhage shortly afterward.

It was later discovered that Gingerich found that many of the first editions contained extensive annotations in the margins that contradict Koestler’s claim, even though most leading mathematicians and astronomers of the time focused on the earlier chapters relating to Copernicus’ cosmology models rather than the later chapters relating to planetary motion. In addition, Westergaard’s copy includes extensive marginal annotations in two different handwriting styles which he believes date from the 16th century. This edition was sold in 1949 by an Italian dealer, Battiata Galanti. The book was sold again in 1970 to private collectors before being purchased at auction in 1983 by Dutch collector Joost Ritman, who created the Ritman Library. Its current owner purchased the volume at auction in 2013.

Westergaard explained that Copernicus was once a book which needed a permit to be read. He added that if a library had a copy, it would be locked away in a little separate cupboard. He has a copy that is not censored at all.

Alexis Boutilier is from Vancouver, British Columbia. She has a high interest in all things tech and loves to stay engaged on all the latest appliances and accessories.