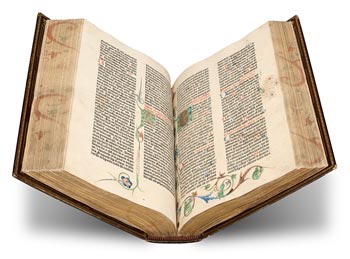

Sometimes, the real news on the internet happens in the comments’ section, all trolls and grammatically incorrect ugliness aside. A post that shared photos of a digitized Gutenberg Bible gave readers a lot of background information into the historical implications of the book itself, as well as an interesting and educated peek into the evolution of language and print.

While much of the conversation is about the Bible itself and the stylistic and grammatical conventions at the time of its writing, a very real concern was raised by the actual digitization, which in this case, is really only professional-quality and non-invasive or destructive photography. The license attributed to the photos of each page indicates, according to one user’s conversation, that it will not be usable online due to terms of use agreements with various websites, including Wikipedia:

According to user huskyr, “Although i applaud the effort of putting this publication online in such a nice, interactive way, i’m a bit saddened to see the license underneath the page leading to a Creative Commons Noncommercial (BY-NC-SA) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/).

“This means that the images are not usable on, for example, Wikipedia, that only allows CC-BY and CC-BY-SA licenses. Also, there seems to be no easy way to get those images and reuse them, apart from reverse-engineering the application and scraping the files.

“Apart from that, adding any license to a work that has been in the public domain (Gutenberg died in 1468) is questionable in terms of copyright law. Reproductions of 2D public domain works (such as this text) are not applicable to renewed copyright law, considering Bridgeman vs Corel (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bridgeman_vs_Corel) and many other similar rulings in other countries.”

To which another user, rmk2, added his reply, as well as his understanding of the current law:

“If I understood the linked article correctly, nobody knows about the actual effect these rulings have on UK law, where this digitalisation originated. Until there has been a similar case brought before the court, little seems to suggest that this is, indeed, not copyrightable?”

The legal battles that have surrounded several different companies’ efforts to preserve rare texts have often included concerns that the text will be widely available for public consumption and manipulation. However, supporters of the digitization of these rare and irreplaceable collections have cited that exact point as the reason to move forward. These pieces of history are cutoff from public, global use, when they could be seen around the world at the click of a mouse.

Mercy Pilkington is a Senior Editor for Good e-Reader. She is also the CEO and founder of a hybrid publishing and consulting company.