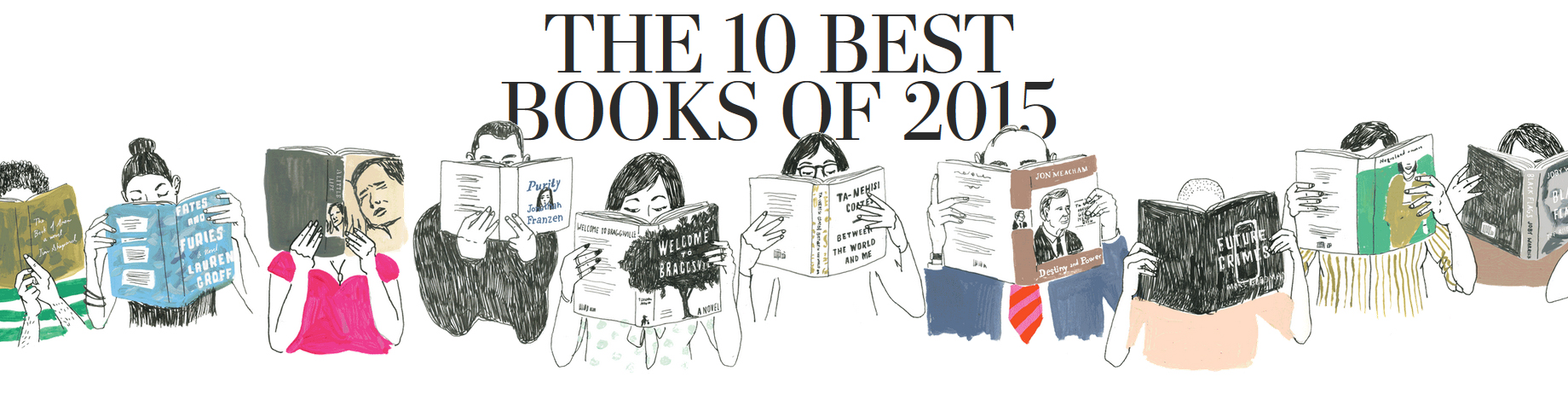

The Washington Post Bestseller List is primarily sourced from data provided by Nielsen BookScan. This company monitors sales from retail stores such as Barnes and Noble Books-a-million, and online sources such as Amazon. The editors at the Washington Post has just released their picks for the top 10 books of the year and some of them are really compelling. Here are their picks for 2015.

Between the World and Me

By Ta-Nehisi Coates

Black Flags – The Rise of ISIS

By Joby Warrick

The Islamic State, whose radical Islamic warriors have inflicted their brutality across the globe from the Middle East to Paris, was founded as al-Qaeda in Iraq in 2004 by a Jordanian thug known by his nom de guerre, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. In “Black Flags,” Joby Warrick, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter at The Washington Post, explains the importance of this gangster and analyzes his continuing influence on the Islamic State long after his death in 2006. There have been a number of previous biographies of Zarqawi, but Warrick takes the story much deeper. Most important, he shows in painful but compulsively readable detail how a series of mishaps and mistakes by the U.S. and Jordanian governments gave this unschooled hoodlum his start as a terrorist superstar and set the Middle East on a path of sectarian violence that has proved hard to contain.

The Book of Aron

By Jim Shepard

In the summer of 1942, German soldiers expelled almost 200 starving children from an orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto and packed them into rail cars bound for Treblinka. Drawing on his imagination and dozens of historical sources, Shepard brings the Warsaw orphanage to life in this remarkable novel about a poor Polish boy and his friendship with the caretaker of the orphans, the pediatrician Janusz Korczak. The novel hangs on the delicate tension in the adolescent narrator’s deadpan voice — never cute, never cloying. Aron relays his world just as he experiences it: “The next morning my father told me to get up,” he says, “because it was war and the Germans had invaded.” And with that news, his town slides into hell. Although relentless in its portrayal of systematic evil, “The Book of Aron” is nonetheless a story of such candor about the complexity of heroism that it challenges us to greater courage.

Destiny and Power

The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush

By Jon Meacham

Jon Meacham’s new biography of George H.W. Bush accomplishes a neat trick. It completes the historical and popular rehabilitation of its subject, though it does by affirming, not upending, common perceptions of America’s 41st president. In Meacham’s telling, Bush indeed lacked an ideological vision, was as overmatched in domestic policy as he was masterful on the global stage, benefited from his family’s influence, and remains overshadowed “by the myth of his predecessor and the drama of his sons’ political lives.” What Meacham so skillfully adds to this understanding — through extraordinary detail, deft writing and, thanks to his access to Bush’s diaries, an inner monologue of key moments in Bush’s presidency — is the simple insight that none of these supposed flaws hindered the man from meeting the needs of the nation and that, if anything, they helped him. Bush sought power less to pursue a particular agenda, the author writes, than to fulfill “an ideal of service and an ambition — a consuming one — to win.” The story of how he did it is worth every page of this hefty volume.

Fates and Furies

By Lauren Groff

Spanning decades, oceans and the whole economic scale from indigence to opulence, “Fates and Furies,” which was a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction, holds within its grasp the story of one extraordinary marriage. The book’s first half concocts the blessed life of Lancelot “Lotto” Satterwhite, the adored son of a wealthy Florida family who has great ambitions to be an actor. His wife, Mathilde, so long impoverished and alone, willingly takes on the chore of encouraging this self-absorbed, quick-to-despair young man. Groff’s flexible style can be impressionistic enough to convey the high points of passing years or lush enough to embody Lotto’s melodramatic sense of himself. And halfway through, Groff turns from “Fates” to “Furies,” and we see Mathilde’s life unmediated by Lotto’s idealized vision of her. Here’s a woman as determined as Antigone, as ferocious as Medea.

Future Crimes

Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable, and What We Can Do About It

By Marc Goodman

Welcome to the brave new world of criminal technology, where robbers have been replaced by hackers and victims include all of us on the Web. Goodman, a former beat cop who founded the Future Crimes Institute, wrote his book to shed light on the latest in criminal and terrorist tradecraft and to kick off a discussion. He presents myriad cybercrime examples: There’s the Ukraine-incorporated start-up that sold what it called an “entirely new class” of antivirus software, which turned out to be crimeware — software that is written to commit crimes. Even the human body is hackable. Researchers successfully broke into a pacemaker and were able to read confidential patient information and could have delivered jolts of electricity to the patient’s heart. In the last two chapters, Goodman suggests how to limit the impact of this new brand of crime and calls for us to tackle cybersecurity in much the same way we treat epidemics and public health.

A Little Life

By Hanya Yanagihara

Hanya Yanagihara’s novel, which was a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction, illuminates human suffering pushed to its limits, drawn in extraordinary, eloquent detail. At the opening, four young men move to New York City. They are devoted to one another, each with bright paths glimmering before them. Despite the brothers-in-arms setup, however, the narrative quickly concentrates on one of the men, Jude, an orphan with a mysterious past who becomes an assistant prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office. Jude’s desire to maintain a veneer of control, despite being haunted by sexual and psychological abuse, creates the book’s major drama. As “A Little Life” paints it, his friends’ love is the thing that could save Jude, if only he would let it. Through her decade-by-decade examination of these people’s lives, Yanagihara draws a deeply realized character study that inspires as much as devastates.

Negroland

A memoir

By Margo Jefferson

Margo Jefferson was an African American girl from a good family that had money, connections and expectations of excellence. She attended Chicago’s private, progressive Lab School, graduated from Brandeis and Columbia universities, and eventually worked at the New York Times, where she won a Pulitzer Prize for criticism. She was (mostly) protected from the sting of racism and its pernicious hacking away at self-esteem, opportunity and hope. Her father was a pediatrician, and she describes her mother as a socialite. But her armor was thin, and over the years she has nursed her discomfort with being a child of privilege. “Negroland is my name for a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered,” she writes. In Negroland, residents were mindful that being perceived as too successful by whites risked provoking their wrath. So they walked through life proudly but with care, treading cautiously so as never to offend. “Negroland” is not about raw racism or caricatured villains. It is about subtleties and nuances, presumptions and slights that chip away at one’s humanity and take a mental toll.

Purity

By Jonathan Franzen

As he did in “The Corrections” (2001) and “Freedom” (2010), Franzen once again begins with a family, and his ravenous intellect strides the globe, drawing us through a collection of cleverly connected plots infused with major issues of our era. That Dickensian ambition is cheekily explicit in “Purity,” which traces the unlikely rise of a poor, fatherless child named Pip. At least partially to escape her mother’s neediness, Pip accepts an internship with a rogue Web site in the jungles of Bolivia that exposes the nasty secrets of corporations and nations. Its leader is an Internet activist whose back story in East Germany reads like a cerebral thriller. Sustaining this for almost 600 pages requires an extraordinarily engaging style, and in “Purity,” Franzen writes with perfectly balanced fluency. From its tossed-off observations to its thoughtful reflections on nuclear weapons and the moral compromises of journalism, this novel offers a constantly provocative series of insights.

Welcome to Braggsville

By T. Geronimo Johnson

This shockingly funny story pricks every nerve of the American body politic. D’aron Little May Davenport, a polite white teen from Braggsville, Ga., arrives at the hypersensitive University of California at Berkeley as if he’s a Southern-fried Candide. The whole novel turns on a moment in one of his history classes when D’aron mentions that his home town stages a Civil War reenactment every year during its Pride Week Patriot Days Festival. A too clever, incredibly offensive, potentially disastrous plan is born: D’aron and three friends travel back to Braggsville and stage a mock lynching, “a performative intervention.” Johnson is a master at stripping away our persistent myths and exposing the subterfuge and displacement necessary to keep pretending that a culture built on kidnapping, rape and torture was the apotheosis of gentility and honor. But “Welcome to Braggsville” is not just a broadside against the South; it’s equally irritated with liberalism’s self-righteousness.

Michael Kozlowski is the editor-in-chief at Good e-Reader and has written about audiobooks and e-readers for the past fifteen years. Newspapers and websites such as the CBC, CNET, Engadget, Huffington Post and the New York Times have picked up his articles. He Lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.