We all know that reading is good for us. It can improve memory, increase imagination as well as reduce stress. According to several studies over the last decade or so, it turns out that reading isn’t just a great way to escape and gain knowledge. Researchers have found that reading involves an elaborate and complex network of signals and circuits in our brains which need to work in unison.

Neuroscience is revealing what happens in our brains when we read, especially fiction; as it has complex narratives, exciting plot lines and lots of emotional exchanges between beloved characters. This research is showing that storytelling can have a major simulating effect on several areas of our brains and can even cause impactful transformations.

Neuroplasticity, is a process that involves changing the structure and function of our brains. It is defined as, “The ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections after injuries, such as a stroke or traumatic brain injury.”

Essentially, our brains are changing all the time depending on what we expose them too. Yes, you can get smarter at any age, and reading is a natural way for us to do so. This is why reading is so important for reducing the risk of dementia and alzheimer’s; it helps us create new pathways into several areas of our brains.

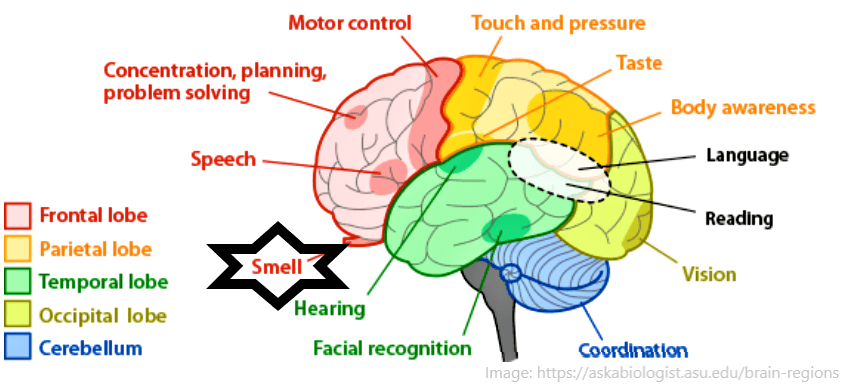

Using scans (MRI’s), we can now see how our cerebral matter engages with many different parts of the brain when we read. When we are first taught anatomy in school we learn about our bodies by studying them as compartments and systems. In fact, much of western medicine still uses this model of “separateness” when approaching health care. For example, if you have a foot issue, you may be sent to a podiatrist. However, we must remember that our bodies are complex, interconnected machines which work as a whole system. When we forget this, we can miss something important. For example, it’s possible to have a sore foot which is actually caused by a pinched nerve in the back.

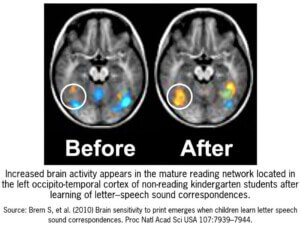

A 2010 study showed how interconnected our brains are when we are first learning to read. The image below is of kindergarten students who don’t yet know how to read. The MRI scan on the left shows a child who has been exposed to the alphabet but not yet taught how to sound-out letters. Without the ability to sound out words, the language centers on the left side of the brain stay inactive, essentially, the brain is stumped on what do with the letters and words on the page.

Whereas, the image on the right is of the same child after they were taught letter-speech sound correspondences. The yellow is blood flow, showing how the brain lights up once the auditory regions are engaged, after the child was taught how to sound-out words.

Another study published in NeuroImage showed that when participants simply read words with strong olfactory associations (smells), the olfactory regions of their brains were activated as if the person literally smelt he smell. For example, when words such as, “cinnamon” and “coffee” were read, they evoked a response not only from the language-processing areas, but also the areas that deal with smells, the olfactory bulb.

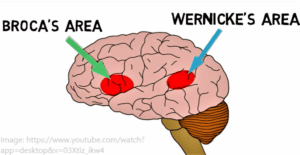

In a really fascinating study, Researchers in France looked at how words that simply described a motion or body movement lit up the motor cortex regions of the brain. When participants read sentences such as, “Pablo kicked the ball” or “John grasped the object”, the brain images showed activity in the motor cortex, which coordinates the body’s movements. What’s even more incredible, is that the word “kicked” affected the part of the motor cortex which was leg-related and the word “grasped” lit up the aspect assoicated with arm movement.

Just like the other studies mentioned, the scans from this study showed our brains don’t distinguish between having a firsthand experience and just reading about it. As shared by The New York Times, “There is evidence that just as the brain responds to depictions of smells and textures and movements as if they were the real thing, so it treats the interactions among fictional characters as something like real-life social encounters”.

All of these studies offer quantifiable proof of something that most English teachers already know, and have been telling their students for years; reading, especially reading fiction, is really good for you. That, and choose books, not drugs.

‘A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads lives only one.’ – George R.R. Martin

An avid book reader and proud library card holder, Angela is new to the world of e-Readers. She has a background in education, emergency response, fitness, loves to be in nature, traveling and exploring. With an honours science degree in anthropology, Angela also studied writing after graduation. She has contributed work to The London Free Press, The Gazette, The Londoner, Best Version Media, Lifeliner, and Citymedia.ca.