According to some projections, ebooks are the reason more people are reading. According to some librarians, ebook lending is the reason more people are borrowing books. So why is the model not working out too well?

The ongoing drama over the Big Six vs. Amazon has left a lot of libraries and their patrons waiting on the sidelines of the debate in confusion, waiting patiently to see when they will simply be allowed to borrow a book. Several other companies, like digital content pioneer OverDrive, have also been dragged into the fray of the “don’t let that ebook touch a Kindle” arguments. Publishers have gone so far as to limit the amount of times an ebook can be borrowed, set restrictions on a waiting period between patrons, and have even decided to forgo ebook lending altogether.

But as more and more consumers have signed up to use their brand-new holiday e-reading devices at their local libraries, they’re finding an even bigger frustration: interminably long waiting lists to borrow ebooks.

There’s a two-fold blame game going on there. The first issue is from the check-out process itself, which is actually supposed to be one of the benefits of ebook lending, especially for many sectors of the reading population who can’t make the trek to a library as regularly as they like. When an ebook is borrowed through the library, the patron selects a pre-determined amount of time to have the book and then the ebook is removed from the device; in some cases, the borrow period is as much as 21 days. Should the patron finish the book only a few days into that three week period, too bad. It cannot be borrowed by the next patron in line until those 21 days are up, which causes a backlog of users waiting for a book that has already been finished.

The second issue is a misconception on the part of the ebook readers. As digital consumers, the public is used to instant access to downloadable media. Movie patrons flip through on-screen movie catalogs from sources like Netflix, television shows are viewable on broadcasters’ websites immediately following the televised broadcast. We are not used to having to stand in line to access digital files. It’s simply computer data, so why the hold up?

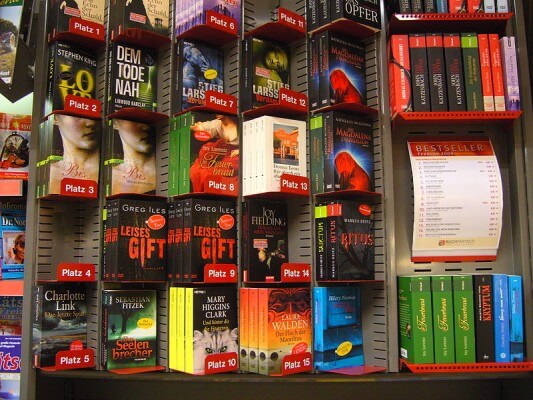

The hold up is because it’s still a book. Despite the fact that it is a file on a handheld device, it is still a book. If a library only has three copies of a bestselling title, there will be a long wait. According to the Washington Post this past Sunday, the Fairfax County Library System had a waiting list of 288 patrons waiting to check out a new John Grisham title; the library system had only 43 copies. It’s a fallacy to assume that because it’s a file that can be uploaded and erased that it is any less a book. There would not be the same irritation over having to wait for a print book because we are conditioned to think of that as an object that must be passed from person-to-person.

Now, libraries are faced with an entirely new dilemma: how much of the budget should be spent on print titles and how much should be spent on ebooks? The demand for ebooks will have to be weighed against the on-site usage of library patrons. In the meantime, hopefully the publishers will come around to the fact that their reading audiences are once again turning to their local libraries.

Mercy Pilkington is a Senior Editor for Good e-Reader. She is also the CEO and founder of a hybrid publishing and consulting company.