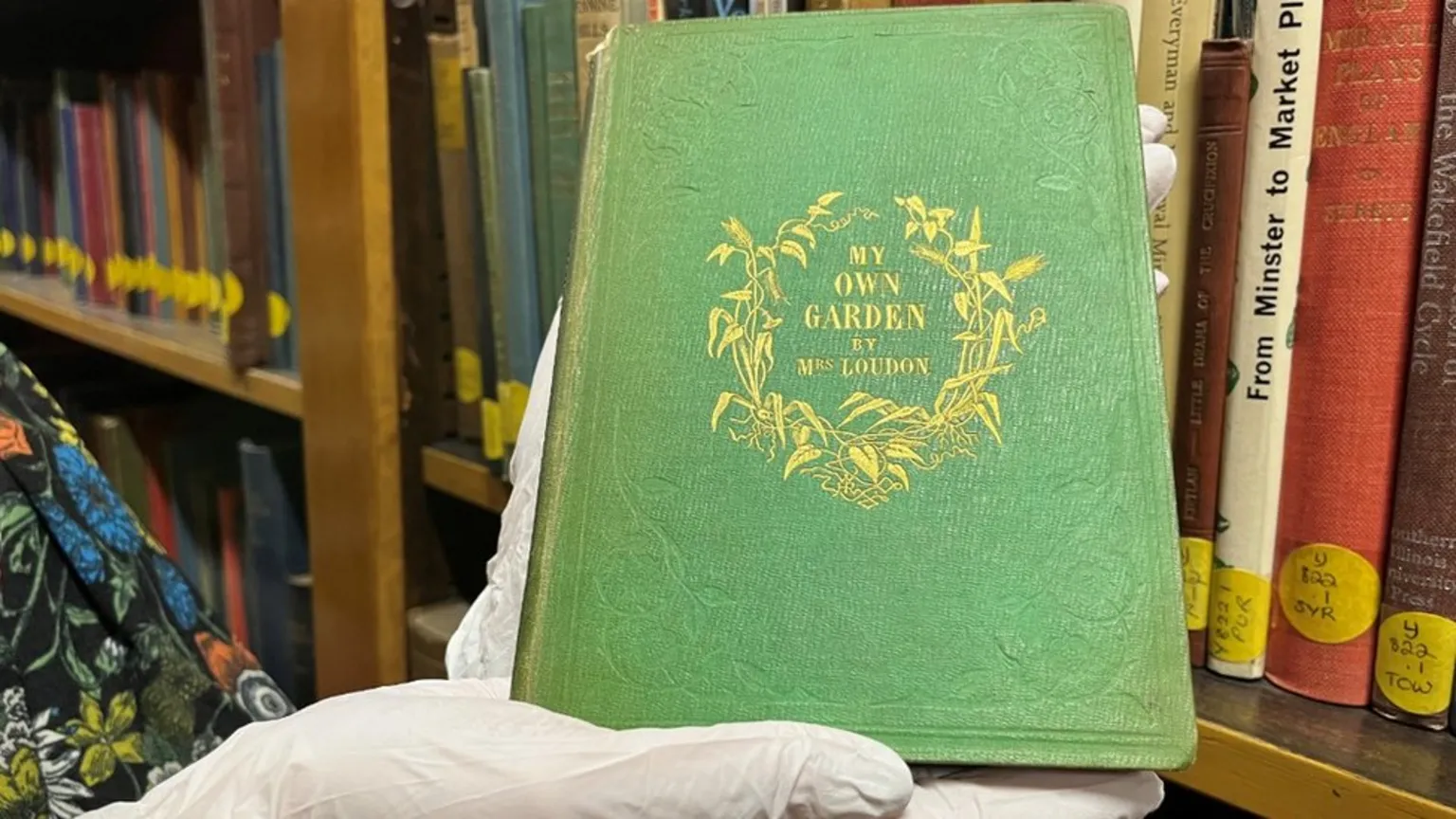

Books published in the 19th Century in Europe and the United Kingdom reflected the prevailing sensibilities of the time. People loved Paris Green, Emerald Green, and Scheele’s Green, named after a German-born chemist. During the Victorian era, pigments were created by combining copper, arsenic, mercury, and chrome to produce striking colors. Unfortunately, the books have survived in archives around the world, including those in France and the United Kingdom.

Most of these books that survived are not typically available for circulation in most libraries and are held in archival collections to be perused but not borrowed. So, there’s a slim chance that anyone would get enough long-term exposure to them to cause any lasting harm, except for the librarians who have worked there for a very long time.

The Poison Book Project was established in recent years to test books and compile a list of titles that are potentially harmful to humans. These included four books in the National Library of France, which were immediately withdrawn. Long-term exposure can cause changes to the skin, harm to the liver and kidneys, and a reduction in red and white blood cells, which can lead to anemia and an increased risk of infections.

How did the Poison Book Project test books? They considered several things, such as X-rays, but found it too destructive for fragile books. They tested a spectrometer – a device that measures the distribution of different wavelengths of light – for detecting minerals in rocks, since minerals and pigments are very similar. After testing hundreds of books, they found a commonality factor. Spectrometers are very expensive, so they built a prototype that shines light on the book and measures the amount of light that shines back. “It uses green light, which can be seen, and infrared, which can’t be seen with our own eyes. The green light flashes when there are no fragments of arsenic present, the red light when there are pigments.” It has already been used to survey the thousands of books in the St Andrews collections and the National Library of Scotland, and the team hopes to share their design with other institutions worldwide.

Poisonous books are not strictly a European problem either. Public libraries in the US and Canada also have a number of these books, but tracking them down can be a daunting endeavour. To find these books, most rely on manual cataloguing, rather than technology. On a Reddit thread, someone said, “I’ve been involved in three inventory projects at the main branch of the Boston Public Library. During the last one, I was an inventory assistant, which meant part of my job was measuring books in a specific collection and taking down other information about the books. Such as, if there was any evidence of emerald green edges, aka possible traces of arsenic. Part of the training involved explaining the history of the emerald green books and the protocol we were to follow if we encountered books that might be contaminated with arsenic. Even though I didn’t encounter it a lot, I still wore gloves.”

Michael Kozlowski is the editor-in-chief at Good e-Reader and has written about audiobooks and e-readers for the past fifteen years. Newspapers and websites such as the CBC, CNET, Engadget, Huffington Post and the New York Times have picked up his articles. He Lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.