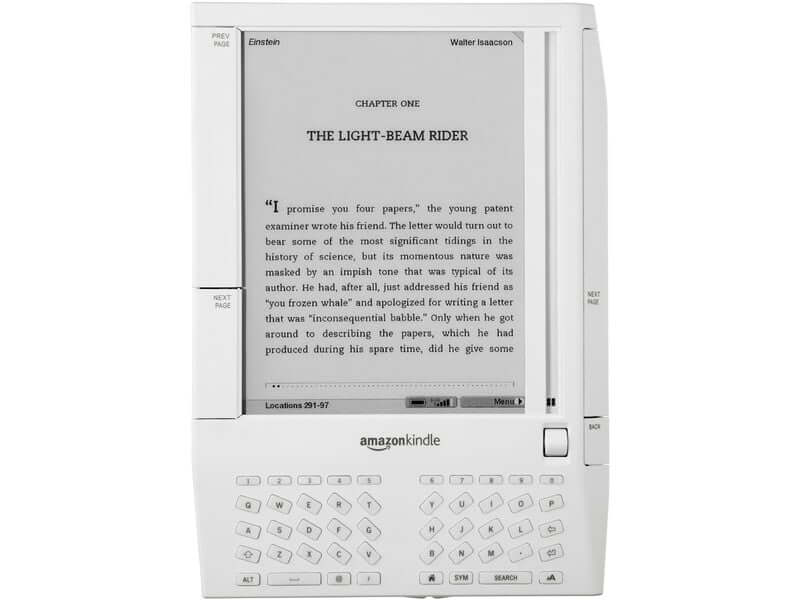

The Amazon Kindle is ubiquitous with the e-reader and enjoys tremendous brand name recognition. It has sold the most units worldwide over the past ten years than any other company and continues to dominate digital books in Canada, UK and the US. Initially the first Kindle was called project Fiona and it borrowed its design sensibilities from the Blackberry, which was mandated by CEO Jeff Bezos. This is the tale of how the very first Kindle got developed and what made it into the juggernaut that is today.

Jeff Bezos was initially pitched the idea of an e-reader in 1997 by NuvoMedia founders Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. They took their Rocketbook prototype to Seattle and spent three weeks in negotiations with Bezos and his top executives. Bezos “was really intrigued by our device,” Eberhard says. “He understood that the display technology was finally good enough.”

Bezos seemed impressed but had some reservations. To download books, a customer needed to plug the e-reader into his computer. “We talked about wireless but it was crazily expensive at the time,” says Eberhard. “It would add an extra four hundred dollars to each unit and the data plans were insane.” The Rocketbook’s display wasn’t as easy on the eyes as modern e-readers, but Eberhard had checked out

low-powered, low-glare alternatives, like E Ink, being developed in the MIT Media Lab, and e-paper, from Xerox, and found the technology was still unreliable and expensive.

After three weeks of intense negotiations, the companies hit a major roadblock. Bezos told Eberhard he was concerned that by backing NuvoMedia and helping it succeed, he might be creating an opportunity for Barnes & Noble to swoop in and buy the startup later. So he demanded exclusivity provisions in any contract between the companies and wanted veto power over future investors. “If we made a bet on the

future of reading, we’d want to help it succeed by introducing it to our customers in a big way,” says David Risher, Amazon’s former senior vice president of U.S. retail, who participated in the negotiations. “But the only way that’d have made sense is if it had been exclusive to us. Otherwise, we’d have been funneling our customers to a potential rival.”

Later on the Rocketbook was picked up a few weeks later by Barnes and Noble and a series of other investors, but the seeds were planted in Jeff Bezos mind.

In 2004 Bezos wanted a cohesive digital strategy to compete against the recently risen Apple computers and he wanted a handheld digital reader and to convince publishers to resurrect the ebook format.

The board of directors told Bezos that sitting on a surplus of unsold units would be disastrous and there would be massive challenges in designing hardware. Bezos dismissed those objections and insisted that to succeed in books as Apple had in music, Amazon needed to control the entire customer experience, combining sleek hardware with an easy-to-use digital bookstore. “We are going to hire our way to having the talent,” he told his executives in that meeting. “I absolutely know it’s very hard. We’ll learn how to do it.

In the book Amazon the Everything Store it said “Throughout Amazon history, there was perhaps no more faithful or enterprising Jeff Bot than Steve Kessel, a Boston-born graduate of Dartmouth College and the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. Kessel joined Amazon in the heat of the 1999 expansion after a job consulting for browser pioneer Netscape. In his first few years at the company, he ran the book category at a time when Amazon was cultivating direct relationships with publishers and trying to assuage their fears about third-party merchants selling used books on the site. During this grinding period of Amazon’s greatest challenges, Bezos grew to trust him immensely. One day in 2004, Bezos called Kessel into his office and abruptly took away his impressive job, with all of its responsibilities and subordinates. He said he wanted Kessel to take over Amazon’s fledgling digital efforts. Kessel was skeptical. “My first reaction was that I already had the best job in the world,” he says. “Ultimately Jeff talked about building brand-new things, and I got excited by the challenge.” Bezos was adamant that Kessel could not run both the physical and digital-media businesses at the same time. “If you are running both businesses you will never go after the digital opportunity with tenacity,” he said. By that time, Bezos and his executives had devoured and raptly discussed another book that would significantly affect the company’s strategy:

Bezos unshackled Kessel from Amazon’s traditional media organization. “Your job is to kill your own business,” he told him. “I want you to proceed as if your goal is to put everyone selling physical books out of a job.” Bezos underscored the urgency of the effort. He believed that if Amazon didn’t lead the world into the age of digital reading, then Apple or Google would. When Kessel asked Bezos what his deadline was on developing the company’s first piece of hardware, an electronic reading device, Bezos told him, “You are basically already late.”

Kessel was credited with forming the secret skunkworks project LAB126 to develop an e-reader. The secret company was run by Gregg Zehr, former VP of hardware engineering at Palm Computing, who took the reigns. LAB126 were basically given unlimited resources by Bezos and were able to hire engineers, designers and manufacturing experts. They researched existing e-readers of the time, and concluded the market was wide open. It was the one thing that wasn’t being done well by anyone else out there.

LAB126 was exploring technology to power their e-reader and settled on using E-Ink, instead of traditional TFT and LCD displays that most of the earlier devices had employed, like the Rocketbook, Softbook and Cybook. In an old interview with computer history, Zehr outlined the process of experimenting with various digital paper displays “We started to explore are these electronic paper displays, so we went and talked to the various vendors that were making them. And what we soon discovered was they were all R&D. Nothing was shipping in any kind of volume. But it seemed like the brand E Ink was ahead of other people. They were sort of a spin out from Phillips. And they seemed to have a leg up. They were startup out of MIT, but Phillips had made some investments and gotten the technology pretty far along. So it was almost ready for volume manufacturing.” The only e-reader to employ E-Ink around this time was the Sony Libre, but it suffered from poor sales.

The Kindle project ended up having the codename Fiona, which was taken from Neal Stephenson’s the Diamond Age, a futuristic novel about an engineer who steals a rare interactive textbook to give to his daughter, Fiona. A funny sidenote, Stephenson and Bezos became friends afterwards and he was an early consultant for the spaceship company Blue Origin.

In order to create the e-reader, LAB126 had to outsource the manufacturing to China, build a supply chain and iron out all of the fine details. There were a lot of things to consider for a V1 project, as Zehr explained “you start to realize, like, oh, yeah, there’s a lot of infrastructure we had to go and build out those business relationships, those technical connectivity issues, the hardware, battery life issues, the software issue, store commerce or on device commerce, straight from the device without any intermediary. Plus, another part of the vision was if you ordered the device, when it comes to you, it already comes pre-configured knowing your Amazon credentials, so you can just turn it on. It wakes up, it provisions out to the network, it goes and presents your credentials to the Amazon store in a secure way.”

The Fiona design was initially contracted out to British firm called Pentagram. They were tasked with studying the physics of reading and how readers turned pages and held books in their hands. Older e-readers were tried out to and they were unimpressed, finding all sorts of shortcomings.

The Pentagram designers worked on the Kindle for nearly two years. They periodically traveled to Seattle to update Bezos on their progress, and they had to present to the CEO and the meetings could get tense. Bezos wanted a simple, iconic design but insisted on adding a keyboard so users could easily search for book titles and make annotations. (He envisioned sitting in a taxi with Wall Street Journal columnist Walt Mossberg and keying in and downloading an ebook right there in the cab.) Bezos toted around a BlackBerry messaging device at the time and told the designers, “I want you to join my BlackBerry and my book.” In one trip to Seattle, the designers stubbornly brought models that left out the keyboard. Bezos gave them a withering look. “Look, we already talked about this,” he said. “I might be wrong but at the same time I’ve got a bit more to stand on than you have.”

Bezos wasn’t initially sold on the idea of 3G on an e-reader, but Zehr managed to convince him. “BlackBerry at the time was using this weird network call MobiText, but they were just moving very

lightweight packets around. It seemed to me like that was a messaging, pager. That was an old pager

network, very low bandwidth, and really not built out all that well. So I encouraged Jeff to look at 3G. 3G was just coming on board for moving digital information around. And so we built up a little, well, not little, this giant honking prototype where we had bought a third party 3G modem, lashed that into our prototype, and demonstrated 3G connectivity into the network.

Pentagram worked on the project until 2006, until LAB126 had hired their own internal design team and fired the initial firm. There were numerous delays, such as a faulty E-Ink order in which the panels would disintegrate under specific temperatures and humidity. Intel sold the family of XScale microprocessor chips that Kindle used, to another chip company, Marvell. Qualcomm and Broadcom, two wireless-technology companies that manufactured cellular components to be used in the Kindle, but they ended up sueing each other in 2007, and at one point it seemed like a judge would prevent certain key Kindle parts from entering the United States. Bezos himself brought about repeated delays, finding one fault or another with the device and constantly asking for changes.

The Kindle was kept secret from everyone else at Amazon and was supposed to go on sale around Christmas in 2006, but Bezos wanted a larger catalog of ebooks to launch with and publishers were very resistant, but eventually came on board. The vast majority of them had to be, ahem, coerced. Amazon threatened to remove all of their books from the store and cease to recommend them to customers. When publishers resisted, Amazon punished them and after a few weeks they came around. All of the big Publishers capitulated to Amazon and their $9.99 price tag for new books, never thinking that the format would blow up and would cead too much control. By the fall of 2007, Amazon was close to the goal of 90,000 ebooks that Bezos wanted to launch with.

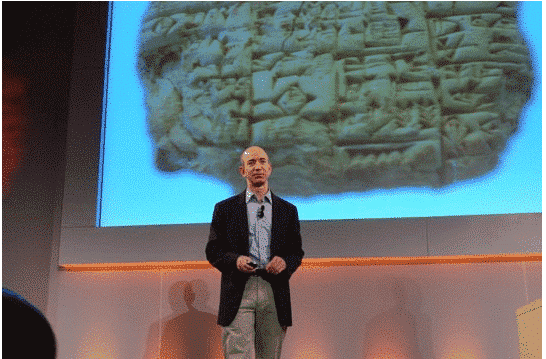

November 19 2007 was the day Jeff Bezos walked on stage at the W Hotel in Manhattan and unveiled the Kindle. There were around 100 journalists in attendance, a far cry from the media circuses that surrounded Apple products. Bezos stated that Amazon’s new device was the successor to the five-hundred-and-fifty-year-old invention of blacksmith Johannes Gutenberg, the movable-type printing press. “Why are books the last bastion of analog?” Bezos asked that day. “The question is, can you improve upon something as highly evolved and as well suited to its task as the book, and if so, how?”

“Instead of shopping on your PC, you shop on the device. The content is delivered seamlessly to the device. Normally you would do Wi-Fi. but you have to find a hotspot. We did not like this technology. decided to use EVDO. As soon as I tell you we are using EVDO that should cause a second set of concerns, because everybody knows there has to be a data plan and a monthly bill. We didn’t like that either. So we built Amazon WhisperNet. it is built on top of Sprint’s EVDO network, but we insulate you from all of those things. there is no data plan, no multi-year contract, no monthly bill. We take care of all that in the background, so you can just read.”

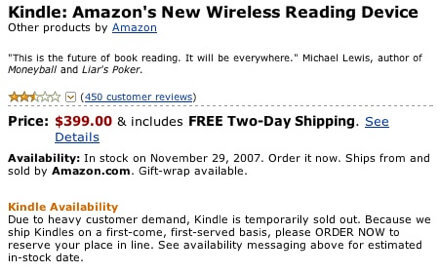

The first generation Kindle was priced at $399.99 and had a wedge shaped design. Of course it wasn’t an overnight success, but an avalanche of publicity and its prominent placement at the top of the Amazon website ensured that the company would quickly run through its stock of devices. Some sources say the initial run of e-readers sold out in five hours. It would take awhile longer to replenish existing stock.

Tech reviewers were very kind to the Kindle. Apple Insider said “If you love books, the Kindle offers a great way to pack around lots of virtual content and grab new content on an impulse buy. At $400, it’s not inexpensive, but it’s comparable to other ebook readers that don’t offer wireless shopping and downloads. The digital books and periodicals Amazon offers are also significantly more affordable than most ebooks that have been offered before, including Amazon’s own Mobipocket catalog. That might play into why Amazon created a new format for the Kindle: to leverage publishers into providing cheaper content using some hype and marketing to generate a larger ebook market than has ever existed before. In that sense, the Kindle strategy does have some similarity with Apple’s iTunes Store.”

ArsTechnica said “For a certain audience, primarily heavy readers and travelers, the Kindle as it stands would make a good purchase. There’s no need to pack several books, and if you find a book isn’t what you’re looking for at the moment, you can easily move on to another, including one you haven’t purchased yet. Anyone who is considering the Kindle in part due to its ability to handle content aside from books should spend some time pondering how much they’d enjoy reading that material within the device’s limitations. Amazon may yet improve the translation of this content to the Kindle reading model but, for now, it just doesn’t work as well as it does in its native medium.”

Macworld said “But, broadly speaking, the Kindle is a game-changing revolution in buying, reading, managing and using electronic books and other content. It’s also the hottest holiday gift you can buy this year for anyone who loves to read.”

The New York Times stated “So if the Kindle isn’t a home run, it’s at least an exciting triple. It gets the important things right: the reading experience, the ruggedness, the super-simple software setup. And that wireless instant download — wow. Even though most people will prefer the feel, the cost and the simplicity of a paper book, the Kindle is by far the most successful stab yet at taking reading material into the digital age. No, it’s not the last word in book reading. But once its price comes down and its design gets sleeker, the Kindle may be the beginning of a great new chapter.”

GIZMODO – Wilson Rothman and Jen Hooker “How comfortable is it to hold? Very comfortable. It’s nice and light. The downside is that it’s very easy to hit the Next Page key accidentally . . . How easy is it to use the scroll wheel? Easy and intuitive. . . How responsive is the keyboard? Turns out, not very responsive . . . How do graphics look on the web? There are two web modes. Default mode lets you see text but pictures come in tiny and hard to see. Advanced mode displays the web page the way you’d expect on a normal browser, but it cuts off text and is harder to manage. Is the screen really “easy on the eyes”? We say yes.”

The Blog.oup summed it up by saying “the commitment that Amazon has shown to give Kindle the iPod effect it deserves is an enormous risk. Amazon has not only committed itself to becoming a device manufacturer (well, at least a branding an OEM manufacturer’s device), it has committed itself to digitizing and converting everything publishers will give them. The combined expense is massive and if it doesn’t show the right return, may deal Amazon a deathly blow that even an 8th Harry Potter book couldn’t fix. The risk here isn’t just to Amazon. If Kindle fails, the ebook is over, the theory of the “iPod model” is wrong for eBooks, and publishing must face the reality that consumers just don’t want to read immersive content on electronic screens of any sort… but let’s not rain on this glorious parade just yet. I think Kindle and the inevitable rivals it will spawn are here to stay. The ebook is dead, long live the ebook!”

Barnes and Noble figured that customers wanted to collect real books and did not see any reason to develop an e-reader or foster relations with publishers to develop ebooks, but they eventually did. Publishers never expected the success of the Kindle and they all thought they gave Amazon too much control over ebook pricing, but for now there was nothing they could do, since they needed the sell physical books on the Amazon platform, and did not want to provoke them.

Over the next decade the Amazon Kindle continues to be the most popular e-reader and most recognizable one in the world. When people ask me what I write about for a living, I tend to say “I write about the disruption of traditional media in the face of digital.” When they ask for clarification I say, “heard about the Kindle before?,” almost everyone says yes.

Michael Kozlowski is the editor-in-chief at Good e-Reader and has written about audiobooks and e-readers for the past fifteen years. Newspapers and websites such as the CBC, CNET, Engadget, Huffington Post and the New York Times have picked up his articles. He Lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.