Mirasol e-paper technology was conceptualized by electrical engineer Mark Miles, inspired by Blue Morpho butterflies, which reflect light using nanoscale structures on their wings that cause incoming light waves to interfere with one another, reflecting only specific wavelengths, resulting in the appearance of an iridescent, brilliant color. Qualcomm bought his company in 2004 for $170 million and refined the technology over the years. It was supposed to take over the e-reader market and give companies a viable color screen, but only four products were ever released. Qualcomm tried to pivot into the internet of things and developed the Toq smartwatch and a concept smartphone, but it failed to get any traction. In 2013 Qualcomm announced that Mirasol would be discontinued, after losing $300 million. They said that they would be open to licensing it, but no products ever materialized. This is the lost history of Mirasol.

Qualcomm Mirasol displays used an entirely different technology compared to conventional backlit LCDs, which create an image by electrically positioning liquid crystals and then shining visible light through it or the more recent OLED, which creates an illuminated image from diodes, requiring no backlight and creating deeper blacks.

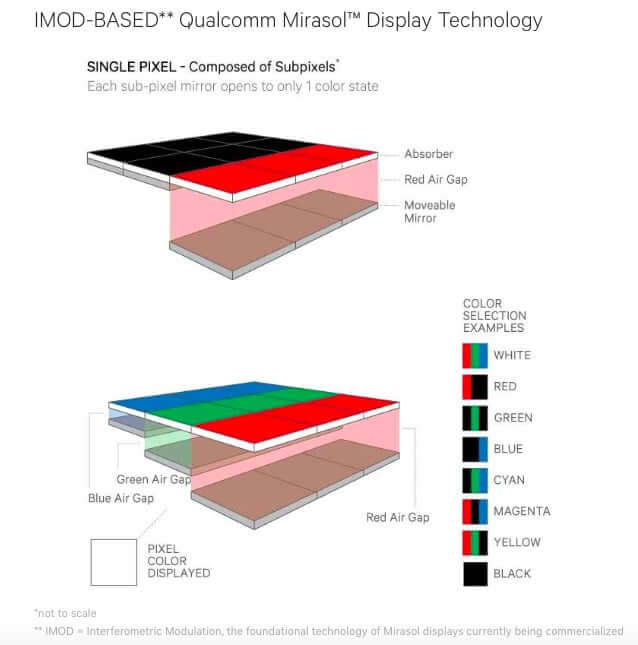

Qualcomm IMOD technology uses an array of microscopic mirror-like elements that can reflect light of a specific color. Like OLED, it doesn’t require a backlight. It also only uses energy when being being switched on or off; once an image is created, it requires no power to refresh or retain it, similar to E-Ink displays used in e-readers like the Kindle.

Also like E-Ink, IMOD technology maintains full visibility in direct sunlight, unlike LCDs and OLED. But rather than moving around dye like an E-Ink screen, IMOD uses tiny moving mirror-like elements, referred to as being a micro-electro-mechanical system, or MEMS (also known as a “micro-machine”). The downside to IMOD has historically been that it reproduces flat, unsaturated colors, a problem that proved impossible to fix before the tech was abandoned.

In order to start commericalzing Mirasol, Qualcomm spent almost one billion dollars on a dedicated factory in Taiwan to produce the screens. It was said that Mirasol displays were relatively easy to produce from a typical FPD (Fabrication and Prototype Design) fab, noting that “the overarching manufacturing benefit of Mirasol display production is that the process was engineered to utilize infrastructure already in place in FPD fabs. All of the materials used for Mirasol display fabrication currently exist within the FPD palette and, in most cases, substitute materials may be utilized. The end result is a flexible and robust process that enables conversion, with minimal modification, of many FPD fabs into Mirasol display foundries, minimizing the time needed to bring IMOD technology to market.

I heard from a former engineer that used to work there that when the production line in Taiwan started to churn out displays, there was a 50% failure rate and the screens were utterly ruined. This is maybe why there were only four different companies that ever adopted the screens in a commercially viable product. Bambook had the Sunflower, Kyobo released their own model and then there was the Koobe Jin Yong and another device by Hanvon.

I reviewed all of these e-readers and found at the time, this was a brave new world of color e-paper. Only Qualcomm and E Ink were developing this type of screen technology, but the colors on both companies products ended up looking really washed out. You can see a demonstration of Triton and Mirasol with a comparison we conducted with the Kyobo and the Ectaco Jetbook Color.

Sadly, these were the only e-readers ever to employ Mirsol and once their initial production run was sold out, they never placed more orders. Mirasol made the call to leave the market to E-Ink, who already had become the market leader and forced Bridgestone, Pixel Qi and Plastic Logic to exit the space entirely.

E-Readers were obviously not the way of the future, instead Qualcomm tried to take advantage of the whole The Internet of Things catch all category. I was one of the few journalists in attendance when ed SID Display Week 2013 occured in my own backyard of Vancouver, BC.

I managed to score an exclusive interview with the new public face of Mirasol, Jesse Burke. He explained that Mirasol technology had an existing roadmap and that it has deviated from it in small ways to brave a new frontier of wearable technology. There were three new products showcased at the event, such as a smartwatch, a secondary screen for a phone, and main screen for a phone.

Qualcomm had to augment the existing Mirasol tech to make it fit on smaller devices. When the tech was employed on e-readers they had two different layers on the screen and made the colors look washed out. Instead after lots of development, Qualcomm managed to merge the two layers, producing rich and vibrant color.

The Mirasol smartwatch was the main attraction at SID and had a 1.2 inch screen that would last a few weeks before needing a recharge. The intention behind this product is not just to tell the time, but to be an extension of your digital life. On average, we reach for our smartphones almost 100 times a day, to check Twitter, Facebook, messages, and missed calls. The watch will ping you with Google Now updates, Facebook Home, and other essential apps. Mainly, it will serve as a secondary screen that will assist you in staying on top of all the action, without constantly referencing your bulky phone.

Smartphone tech was another big gambit for Mirasol screen technology and they really hyped to me that the average phone has a battery life of 12-24 hours, depending on your use. Mirasol will extend this up to six times, which amounts to hefty savings over LED and OLED screens.

There were two phone displays shown at SID, one was a fully featured smartphone, using Mirasol, and the other was a second display screen on the back of the phone, that draws parallels with the YotaPhone. The smartphone had sported a 5.1-inch panel with a stunning resolution of 2,560 x 1,440 pixels and 577 ppi. The second display was on the back of the phone, and mirrors the watch in terms of form and function. It allows you to have a secondary screen with dedicated apps running on it. Useful, but it remains to be seen if multi-screen smartphones are viable with your average consumer.

Qualcomm never released any of these products on their own and tried to find companies that wanted to license the technology to develop their own products. The phones and smartwatch were merely a proof of concept that never went anywhere.

A number of companies announced smartphones that were going to use Mirasol, such as the Cal-Comp iT-810 and the Inventec V112, but they never materialized.

The Apple Connection

In 2015 Qualcomm took a $142 million charge on its Mirasol display business, when it could not find anybody to license their technology and the smartphone and tablet market became firmly entrenched with LCD and OLED screens.

Records from the Hsinchu Science Park management office, which manages the Longtan facility where Mirasol display products were manufactured, show Apple moved into the factory in April 2015 and that Qualcomm Panel Manufacturing Ltd. had occupied the site from 2008.

It was said at the time that Apple poached many of the engineers that used to work there to make their iPhone and iPad products slimmer and have better battery life.

Mirasol, what might have been

Many of the former executives and engineers that used to work at Mirasol are jaded from the time invested working on a technology, that never went anywhere. They have a hard time even talking about it.

At its peak Mirasol had cross-functional teams in San Diego, San Jose, Hsinchu, and Longtan. They had grand ambitions for the technology, but shareholders were tired of the division constantly losing money. Qualcomm instead decided to power the smartphone revolution with their Snapdragon processors, which continue to be the industry standard.

I think many people do not realize the effect that Mirasol had on the e-reader revolution. Over a few short years they were a major player in color e-paper and it was thought they could give E Ink some serious competition. E Ink had the largest customers at the time, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Sony and many of the European brands. Mirasol had South Korea and China firmly locked up and if they would have sorted out their production woes, they really could have amounted to something great. Instead, they abandoned E-Readers, tried to capitalize on the whole internet of things category and quickly suspended development on everything. Too many failures and not enough market penetration resulted in Mirasol becoming a lost technology, that few people will ever remember.

Michael Kozlowski is the editor-in-chief at Good e-Reader and has written about audiobooks and e-readers for the past fifteen years. Newspapers and websites such as the CBC, CNET, Engadget, Huffington Post and the New York Times have picked up his articles. He Lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.