When people (re: students) complain about the outrageous cost of higher education, they’re usually referring to astronomical tuition increases, seemingly endless student fees, and of course, multi-million dollar bribes to get Junior into his party school of choice. What is often overlooked at first is the inexcusable cost of textbooks, which have risen by more than 88% just since 2006.

Why are textbooks so expensive? After all, Shakespeare hasn’t written anything new lately, and any profoundly-updated commentary on the plays will most likely not be read by a freshman literature student anyway. That’s why some sources point out that literature books and those in other arts-related fields cost less than books whose subject matter is often updated or changed with new discoveries or advancements, such as STEM-field titles.

Still more of the cost involved comes down to basic supply and demand. While people line up to purchase the latest bestselling fiction title from a top author, that’s less true for a recently published Spanish 101 textbook. In order to meet the costs associated with writing and publishing The History of Early Film, it sells for slightly more than three car payments (around $740).

Like too many other things that hit lower- and middle-income consumers the most, textbook prices have far outpaced the rate of inflation. It’s not just that wages haven’t increased at the same pace, but that even other consumer goods haven’t increased as quickly or as much as textbooks.

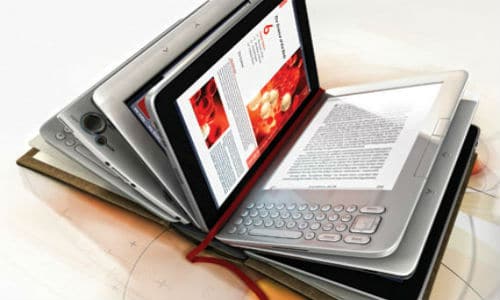

The digital publishing revolution was supposed to alleviate the problem of staggering costs, if not eliminate it altogether. Unfortunately, educational publishing is a closed shop; the publishers set the price, the professors agree to use whatever materials they’re “encouraged” to use, and the students bear the brunt of it. Worse, digital publishing has created an even more sinister, highly expensive problem: access codes.

Not content with merely selling the print edition, publishers now offer–and some professors require–the students to purchase the access code to accompany the textbook. The code, which can cost as much as the print book itself, offers supplementary materials, otherwise known as “all the things that digital textbooks were supposed to include in the first place.” These codes are one-time-use, and have decimated the students’ ability to get any kind of return from selling their used textbooks.

Fortunately, the current “Millennials are killing every industry” trend is already infecting educational publishing. Some universities and professors are even beginning to take a stand against the outrageous costs of materials, and platforms have sprung up to offer free and open source college materials. Some curricula even rely solely on original or permission-based Google Docs to provide students with reading material. Basically, they’ve taken up the slack where the industry was supposed to revolutionize and equalize education.

Mercy Pilkington is a Senior Editor for Good e-Reader. She is also the CEO and founder of a hybrid publishing and consulting company.